Framed in Nature | The Evolution of Scientific Inquiry & Natural History Artwork from the 17th–19th Centuries | The Jessica Ehmann Collection

September 12, 2013 - November 9, 2013

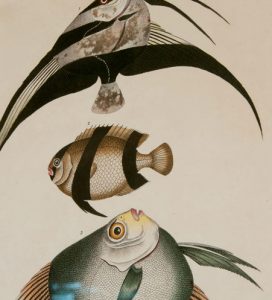

A unique nexus of art and science, the art of natural history emerged during the Renaissance from the extraordinary collections comprising “Kunstkammern” or “Cabinets of Curiosities” accrued by European monarchs, affluent merchants and certain men of science. A Cabinet of Curiosities was not, as the name appears to suggest, centered around a piece of furniture, but rather a meticulously curated room filled with carefully displayed objects belonging to the categories of Natural History, Geology, Ethnography, Art and Archaeology. While representing the natural world on a small enough scale to fit into a room, a Cabinet of Curiosities also symbolized its owner’s knowledge of and control over this world through its microcosmic representation. These collections were the precursors to museums.

The popularity of the art of natural history gained momentum in the 18th C. during the Age of Enlightenment. The rationalism, neoclassicism, and emphasis on scientific inquiry characterizing the Enlightenment facilitated the production of significant written works by leading scientists who sought to categorize and make sense of the natural world. A collaboration between naturalists and leading artists of the day represent the high water mark of the genre, and included volumes such as Basil Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis, Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosibus Insectorum Surinamensium and Albertus Seba’s Locupletissimi Rerum Naturalium Thesauri.

In this pre-photographic age, the descriptions of specimens filling these volumes were accompanied by exquisitely beautiful copper-plate engraved and hand-colored artwork. Staggeringly expensive to create, a common thematic thread running through this historiography is how frequently the authors of these volumes and their patrons bankrupted themselves in this pursuit.

Jessica Ehmann on the collector’s view

I find the extraordinary, dazzling array of form, design and pattern to be endlessly fascinating. I have always been struck by the compelling contemporary look of many of these centuries-old works of art. Science, to an extent, drives the finished form of the artwork—a rendered specimen is distilled down to the elements essential for its proper identification, taking on a slightly abstracted look. Further enhancing the modern look of the artwork, the two-dimensional renderings appear to be pushed to the surface of the picture plane, often symmetrically arranged against a blank background. When I look at these pieces, I see modern-looking graphic forms which read beautifully on the wall, even at a distance.

Framing my work

I believe that modern picture frames too often lack the patina, quality of craftsmanship and beauty necessary to properly house this genre of art. Therefore, I have relied as much as possible on the use of original 19th C. American and European picture frames to present the artwork, taking the opportunity to use traditional framing techniques such as French Matting to further enhance and repeat the wonderful array of patterns and textures integral to the artwork. For example, the stenciled Greek Key pattern found on the outer portion of this pair of 19th C. American gilded picture frames echoes the checkerboard pattern found on the Mantis wings in Pl. LXVII, while the stenciled pebble pattern within the cove of the frames repeats the spotted motifs located on the wings of the moths in Pl. XXV.